July 2019

Preserving Free Speech in Education

July 2, 2019

[I]t is hazardous to discourage thought, hope and imagination; that fear breeds repression; that repression breeds hate. . . If there be time to expose through discussion the falsehood and fallacies, to avert the evil by the process of education, the remedy to be applied is more speech, not enforced silence.

-U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, Whitney v. California (1927)

Freedom of speech and expression are among the most cherished and preferred freedoms of the U.S. Constitution and American society. With little exception, those who study at, work for, or visit public educational institutions are afforded those rights.

In March 2019, President Trump issued an executive order that would take away funding from colleges and universities that do no protect free speech. The U.S. Constitution already requires that of public institutions, but this executive order would expand the requirement to private institutions. (The requirements as well as the enforcement mechanisms of that order remain amorphous.)

Some states have issued similar calls, passing legislation that would protect campus free speech, mainly outlawing “free speech zones” which seek to confine speakers to a specific spot on campus. Free speech zone policies have traditionally been struck down by courts as unconstitutional, such as the policy at Texas Tech University, which designated a small gazebo as the only location for free expression on campus.

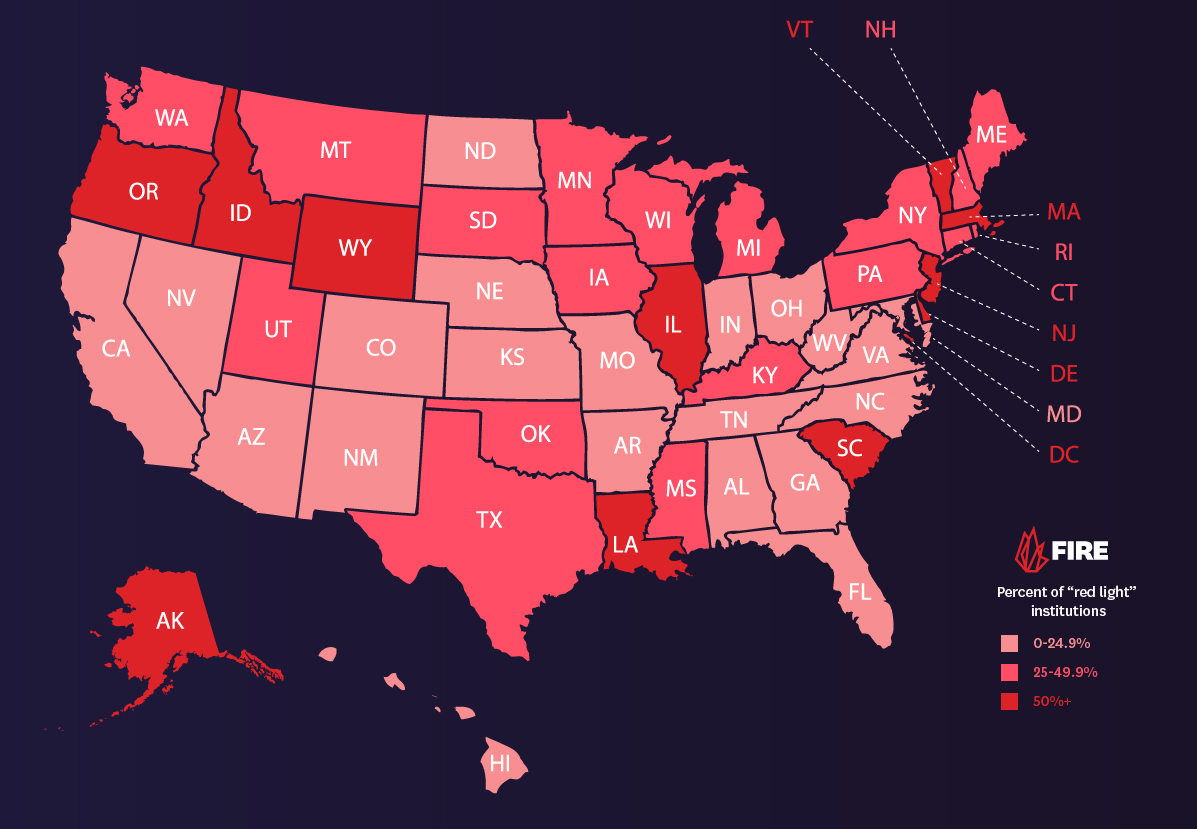

In fact, a recent study by FIRE—Freedom of Individual Rights in Education, a nonprofit legal group which advocates for and defends the rights of students and faculty to free speech and due process in higher education settings—found that 9 out 10 campus policies violate free speech and expressive rights.

What are the bedrock principles upon which campus free speech is based?

Any gatherings, tabling events, or protests must be allowed on public college and university campuses, just so long as they do not disrupt classes or the regular business of the institution. Under the time, place, and manner theory, administrators should ask speakers to relocate, rather than remove them from campus or arrest them.

If LSU has a policy that no students in the residence halls may display flags in their windows, this policy must be equally enforced, whether the flag be that of the Confederacy, supporting Donald Trump, the LSU Tigers, or teddy bears. As U.S. Supreme Court Justice William J. Brennan, Jr. famously wrote in the 1989 decision Texas v. Johnson, “"If there is a bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment, it is that government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea itself offensive or disagreeable."

The University of Mississippi, attempting to reverse its negative public image regarding race relations, wanted to ban spectators from waving the Confederate flag in its football stadium. However, expressive speech—such as flag-waving—enjoys the same protections as spoken or written expression. The university could, though, ban sticks, along with umbrellas, out of safety concerns for spectators.

In another instance, Richard Spencer’s August 2017 visit to the University of Virginia sparked rampant violence, leading to the death of one person. However, unless a speaker is directly inciting the crowd to violence, only those who choose to violently react to the speaker’s message can be punished under the law.

The mere fear that a speaker may disrupt a campus environment does not legally justify restricting the speaker’s right to speak—or the audience’s right to hear the message. When Auburn University sought to ban Richard Spencer from speaking on its campus, well-established First Amendment principles made it easy for a federal district court to issue an injunction preventing that.

The disruption standard was established by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1969 in the landmark case Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District. After a local school board was tipped off that a number of students were planning to wear black armbands to protest the Vietnam War, the school district enacted a policy that any student wearing an armband would be suspended. The Court ruled that the policy was not viewpoint neutral, as it sought to punish the expressive speech of those who espoused a particular opinion of the Vietnam War, and that the mere fear of disruption was not enough to warrant discipline—that the speech must be proven to “materially and substantially interfere” with the regular operation of the school.

Mary Beth and John Tinker were among five plaintiffs in a Vietnam War-era case that established landmark principles for students’ expressive speech rights in schools.

The author had the opportunity to hear Mary Beth Tinker speak at a conference in November 2018. Tinker still travels the country speaking on behalf of free speech rights. - Photo credit: Joy Blanchard

The Tinker case continues to be applied in both the higher education and K-12 settings. Free

speech and expressive speech principles are generally the same in K-12 school settings,

though courts do provide special deference to educators to regulate speech in the interest of pedagogy, as well as to administrators to maintain effective control over the educational environment.

Courts recognize the age of school children and the amount of control school districts are expected to maintain over students—as opposed to college-age students—the U.S. Supreme Court has still upheld that K-12 students do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” So when school administrators seek to monitor student publications, assemblies, expressive speech via clothing, or even commencement speeches, the same tried-and-true First Amendment principles hold steadfast today.

So how can K-12 as well as postsecondary administrators promote safe and inclusive learning environments without violating First Amendment principles?

Restrictive regulations and policies do not appear to be the answer. (Noting that attempts to institute hate speech policies have consistently been ruled unconstitutional, finding that such restrictions would punish ordinarily protected speech and suppress the classroom from being the free “marketplace of ideas.”)

I would point back to the indelible and timeless words of Justice Brandeis—that the remedy to offensive speech is not censorship, but rather more speech. When the University of Oklahoma was called on again to respond to students’ racist utterances—which it did by disciplinary measures, violative of both free speech and due process principles—the President of Dillard University beseeched university presidents to address intolerance by fostering dialogue and changing culture. In a political climate in which First Amendment principles are constantly threatened, it is imperative that educational institutions preserve free speech rights by preserving the rights of speakers and audiences alike by avoiding the easy solution of censorship—or what noted constitutional scholar Erwin Chemerinsky labeled as the free speech-hate speech trade-off—and by rather embracing the free exchange of ideas necessary to preserve active citizenship.

Written by:

Joy Blanchard, PhD | Associate Professor, LSU School of Education

Joy Blanchard is associate professor of Higher Education Administration and editor of Controversies on Campus: Debating the Issues Confronting American Universities in the 21st Century.